Before we jump into the question, I would like to outline how this post will look a little bit different than my previous posts. As I have started building my blog and thinking about my role as an educator at a more professional level, 2 things have been made clear to me. 1) I have a lot to learn, and 2) to become a true professional, a true master teacher, I must learn through the experience of other teachers I respect and admire. Just as a student needs the teacher to help focus their learning, so do I need to lean into the experience of other educators. I plan to explore the central question of this post as a first foray into the process of learning explicitly from my colleagues and peers in the world of education. Supplemented with this question will be a follow-up: “What is the point of a school?”

Over the next few weeks, I will gather responses from fellow teachers within and outside of my current institution. A portion of my collected responses will come from fellow middle school teachers in my department, but the majority of these responses will come from colleagues across all levels of education and will include a sampling of former teachers of mine. Consider this short series of posts a “before and after.” Below, I will answer the above questions based on my current analysis. Afterwards, I will publish at least two additional posts (one for each question) where I explain and analyze my findings, and comment on how my understanding of a school has changed after speaking with colleagues. Let’s get into it.

First, we should define what a school is. For the sake of time and sanity, I’m going to stay away from the broader history of “education” and focus solely on the idea of what a traditional school is. I will briefly examine the roots of modern global education and give my thoughts on what schools should prioritize.

The modern idea of school is, well, modern. As we know them, schools are centralized buildings and campuses where students go multiple days a week to “learn” and “study” within a controlled environment. School is mandatory and students usually learn from a single teacher who is in charge of the learning process for each subject. Students take a curriculum of subjects and are assigned a letter grade that represents the degree to which they have understood the subject’s content. They attend school roughly 180 days a year for thirteen years before they “go off into the real world.” Sometimes the real world means even more school, where some professions mandate another 10 years of formal education. While at school, students’ lives are fairly regulated. They have a predetermined schedule based on core subjects within the curriculum and a smattering of self-selected (or not) electives. They learn expectations for behavior, enhance their social skills, and move around based on an organized routine. The curriculum, as chosen in some sense by the culture-at-large, and in combination with the additional disciplinary and organizational systems put in place by the institution, hopes to turn students into “well-rounded citizens who can contribute to their society.”

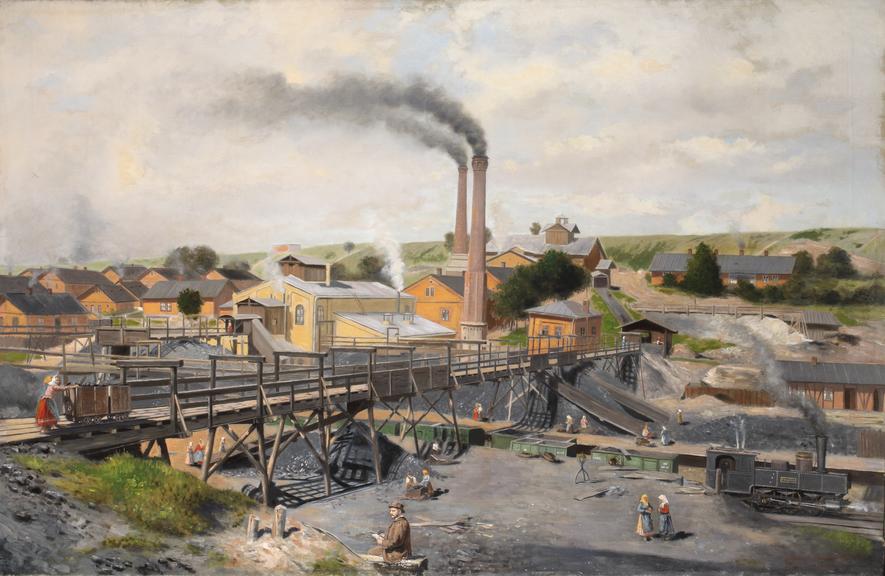

When and how did this modern system of schooling start? The roots of the current system can be traced back to early 19th century Prussia, where the idea of tax-funded, compulsory, and secular education had taken root. An early version of this model was established in the late 18th century by the Prussian, King Frederick the Great. By the early 1830s, it had evolved into the foundations of a system that would be adopted by educational reformers in the United States and across the Western world.1 Early educational reformers in the United States, like Horace Mann, even traveled to Germany in the early 1800s and used it as a blueprint for state and national public education systems.2 This method was then brought back to the United States, and the first Prussian-style education system was implemented by Governor Edward Everett of Massachusetts in 1852.3 From there the system was implemented across the United States and Europe. Over the next century-and-a-half, this model quickly became the de-facto public school system in countries around the world.

Looking at the roots of our system, it is fairly easy to determine why the Prussian model took hold. It is in the best interests of any leader (or emperor) to instill a sense of loyalty among their followers. By establishing a system of mandatory education, the state (in this case Prussia) is free to choose the values and knowledge that it instills in its citizens. If all citizens share a common understanding of the world, their country, and their community, then the bonds between individuals become stronger and thus tighten the broader social fabric. Schools are one way in which cultures share values and experiences, thereby promoting unity and love of country. While the methods and means through which federal, state, and school governments instill this shared sense of identity have certainly changed, it is easy to understand the school as a tool of the state.

Putting the Prussian model in its proper historical context helps us understand the economic reasons for its growing popularity in the Western world at the time. With the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, a new form of labor became commonplace: the factory worker. As the law of supply and demand became entrenched in developing market economies, producers and manufacturers could rapidly increase production and flood the market with consumer goods. This increased demand for goods necessitated an increase in the demand for labor. The bones of an educational system that could meet these demands were already in place and the gradual adoption of the Prussian model meant that producers now had a steady and growing stream of young adults who could enter the workforce. These workers were well-disciplined, and well-mannered, and had been taught under a system that prioritized obedience. This was exactly the kind of worker the new industrial machine needed to thrive.

There are also practical and perhaps less Marxist explanations for the growth of the Prussian model. First and foremost, there just weren’t a lot of other models to choose from. Education systems have been around for centuries, whether it was the philosophical schools of Ancient Greece or the civil service examination system in China. For millennia, cultures have understood the need for at least a small body of educated people, especially within government. Yet, the Prussian model was unique in that it created a national, compulsory, and publicly funded system of schooling designed for the general population. Finally, there was an educational model that could be implemented at any level, whether within a whole country like Prussia or by individual state governments, as was the case in Massachusetts. If the world gives you lemons, it makes sense to first make lemonade.

By this time, the ideals of the Enlightenment had firmly taken root amongst the well-educated and had found their way into the broader populace as well. A slow and steady evolution of these ideals like freedom of expression, freedom of religion, separation of church and state, individual liberty, the idea of a nation-state, and the social contract had created a landscape that was ripe for a national educational system. Coupled with changes brought on by the Scientific Revolution and the development of capitalism, the intellectual class at the time could justify the creation of these broad-based public education systems that taught the 3 R’s. (reading, writing, and arithmetic)

Now that we’ve outlined a short history of the creation of the modern school and explained how this system was created, let’s get to what I think. A school at its core is centered around two groups of people: the student and the teacher. Without these two groups, a school does not exist. Therefore, in deciding what the point of school is and thus deciding what a school is, we must identify the ideal kind of teacher and student. Luckily, we’ve already discussed this in previous posts and have a starting point from which we can answer our central question.

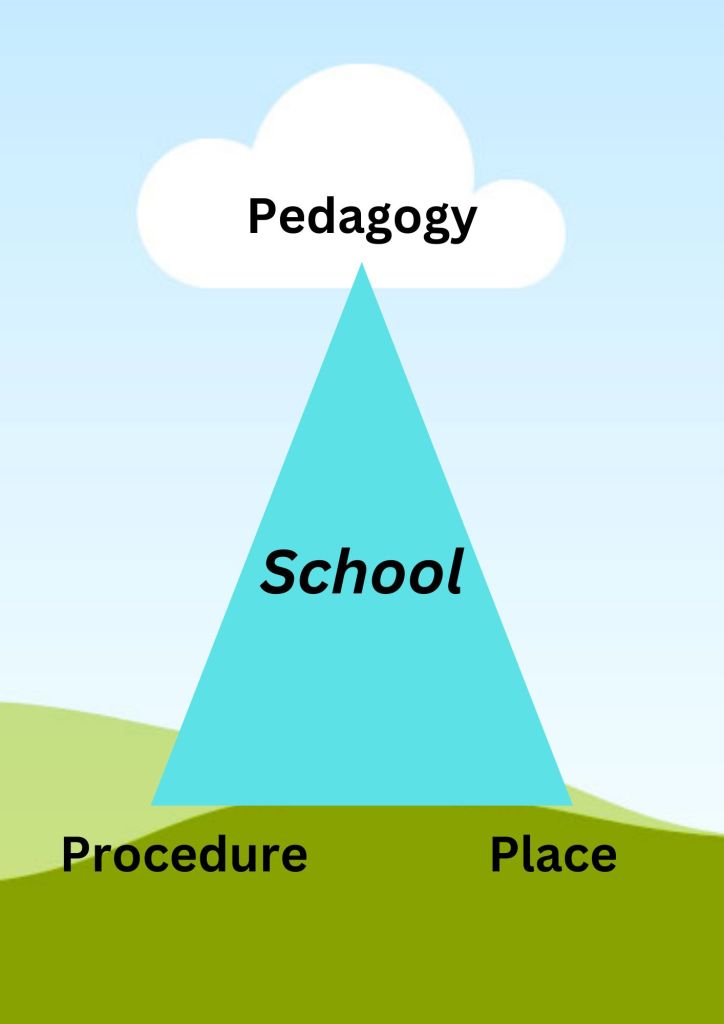

Teachers are leaders and masters who demonstrate excellence in a specific subject and help students learn by modeling the skills, knowledge, work habits, and approach of a master. Students are learners who, at their best, pursue knowledge and skills within a given subject area indefinitely. As they continue their study, they must do the work of a master to successfully acquire said skills and knowledge. To this end, it is the responsibility of schools to ensure that teachers and students have the necessary tools and support. How can schools do this? Instead of the 3 R’s, schools can focus on the 3 P’s: Place, Procedure, and Pedagogy.

Place is literally the physical setting and environment in which the learning happens. To continue with the mastery theme, schools should design settings that are directly related to the work of a master in the subject. In some sense, one can think of an ideal school as a web of apprenticeships. With the teacher playing the role of master and the student the role of apprentice, the physical space should reflect the systems of thought that happen within the subject. The physical place puts students and masters equally “in the mood” for learning about the subject. Ideally, the art class should take place in a gallery or art studio, the music class in a concert hall or recording booth, the science class in a laboratory, and the business class, well, at a business.

Unfortunately, society has not yet developed the necessary systems for this to be possible. The physical setting of schools still represents that of the old model. Students sit in an isolated room with bland walls and perhaps only one window. These rooms actively de-stimulate student thinking and it’s no wonder that many students consider school to be analogous to a prison. In terms of whole-school structure, I’m a big fan of how many college campuses are laid out. Colleges often organize themselves into “hubs” where the design, feel, organization, and architecture reflect the themes of their subjects. Many K-12 schools already do this by organizing school departments into “wings” where one section of the school is the center for related subjects (for example a STEM wing, Humanities wing, or Arts wing).

A small, but perhaps effective addition to this that I think would specifically work with K-12 schools involves the locker. Many schools, (in fact every school I’ve been in) have a locker for each individual student. Lockers could be strategically placed in and around these subject hubs, and students who are interested in that subject can choose to have their lockers in that part of the school. Even between or outside of class, students are immersed in hubs that specifically cater to their academic interests. This could potentially boost academic engagement, while also promoting broader student-student interaction. Because students are no longer only grouped by personality or other social factors, they can now develop stronger relationships with students whom they may have nothing else in common with other than their mutual love for math, history, PE, drama, or another subject. Another potential benefit to this idea is that it creates an atmosphere of academic “closeness” that can facilitate learning in the classroom. When students know who else in the class has a shared level of skill, knowledge, or interest in a particular subject, they will naturally gravitate towards those students when work time begins. This could promote deeper learning because now students are more engaged in collaborative work and operate from a common point of reference.

Procedure includes all operational systems necessary for the daily functioning of the school. Procedure facilitates everything that happens inside the institution and when implemented properly, procedures are reflected in the actions taken by staff and students. A well-implemented procedure is also easily identifiable by people outside the day-to-day workings of the institution. I’m against the corporatization of education in many ways, yet a highly functional school should resemble the systemized and goal-oriented approach many corporations use. Of course, schools cannot adhere, nor should they, to the profit-driven and efficiency-obsessed structure of a corporation. After all, learning is the fundamental goal and students cannot be expected to think or act in a totally systemized way. Schools should seek to cultivate the creativity of their students and as we know creativity always has a tenuous relationship with order. Notwithstanding schools, optimized systems are a strength for any successful organization.

What procedures should schools implement? I think a better question is, what system of systems (think meta-system) should schools use to create and establish a concrete set of principles from which decisions are made. First, the priority must be student learning. This seems obvious, however after just a few years of teaching, it is clear to me that not all schools truly prioritize this. Throughout the educational world, we are seeing an increase in the access of education and educational resources, yet in the United States for example, this increased access to education is not producing skill or knowledge growth in our students. Anecdotally, many teachers I speak with loath the fact that students across all levels are demonstrating a concerning lack of growth in literacy. There are a multitude of reasons for this, and not all of those reasons can be placed on the schools themselves.

Secondly, schools must be process-driven. I may be breaking from traditional wisdom, which holds that results are of utmost importance. Results matter, and my point is that well-defined processes and procedures help get those desired results. Practices that do not result in student learning should not be implemented. At the same time, learning is a result of proven practices. Importantly, a school that is process-driven can better meet the needs of teachers, administration, students, and community members, as a focus on process necessitates the development of systems that are flexible, adaptable, and robust. Results only matter if the systems that lead to them are flexible enough to change in the moment and whenever necessary. Adaptive schools not only seek consistent growth but can change their systems to meet the moment. When effective policies and procedures are put in place, the results will come. Any professional will tell you that it is a master process that leads to master results. When the results do not reflect intended outcomes, I believe it is a sign that processes are not set up in a way that leads to success. If a school wants to create a successful culture that can work for all stakeholders, it must create systems that allow those stakeholders to do their jobs well.

At the end of the day, school is about teaching and learning. Therefore, pedagogy must be the number one priority of any school. This requires several things. Teachers, admins, parents, and the broader culture must be in agreement about how students should learn. They must also be in agreement about what is learned, yet from the school’s perspective, the methodology takes precedence. This starts with administration. In one of my previous posts, I mentioned that administrators should require a stated teaching philosophy from each teacher and should actively work with the teacher to put that philosophy into practice, providing guidance when necessary. Therefore, teachers must be honest in the self-assessment of their craft, seeking ways to enhance the strengths of their particular style while also pushing themselves to grow and develop in the same way students are asked to. Again, this is where the teaching philosophy is so critical. By defining what a good teacher is, he or she can effectively reflect on their practice and work towards that vision in a more focused way.

When teachers and administrators have clearly outlined their pedagogical goals, the school will thrive. When teaching towards mastery, each teacher will have their own particular style. If these individual teaching styles are nested within a school-wide culture of self-development, the school becomes a place where students go to grow alongside their teachers. Just as the apprentice learns by imitating the moves of the master, the student will learn from the approach to learning that the teacher models.

In summary, modern schools are still very much flawed. Many, still derived from the Prussian model of obedience and standardization, do not reflect the values of an education system that puts learners first nor does it create a broader culture of lifelong learning. However, when schools holistically connect their place, procedures, and pedagogy, students are the real benefactors. Administrators have the time and energy to establish a clear and realistic mission that meets the needs of the broader community. Teachers have the intellectual freedom to demonstrate mastery in their subjects and pursue continued self-development. Students are excited because they know they will be learning in an environment that encourages them to ask and answer the essential questions that fit their interests. When place, procedure, and pedagogy are aligned, a new kind of school is born. A school of, by, and for learning.

- Chen, Grace. “A History of Public Schools.” Public School Review, March 7, 2022. https://www.publicschoolreview.com/blog/a-history-of-public-schools.

↩︎ - Donk, Karel. “The Origins of the American Public Education System – Horace Mann the Prussian Model of Obedience : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive, February 8, 2021. https://archive.org/details/the-origins-of-the-american-public-education-system-horace-mann-the-prussian-model-of-obedience.

Online video ↩︎ - McGuigan, Brendan. “What Is the Prussian Education System?” Cultural World, September 3, 2023. https://www.culturalworld.org/what-is-the-prussian-education-system.htm.

↩︎