As mentioned in a previous post, I have been meaning to take a larger view of this question and see how colleagues, past and present, would answer it. These colleagues of mine are of all different ages, nationalities, experiences, and subjects. They reflect the beautiful diversity that one sees when working as an international teacher, conversing and educating alongside professionals from countless backgrounds. This is one of the most exciting and interesting parts of teaching abroad, as one can see how cultural attitudes towards education manifest themselves in practice.

After weeks of data collection (and months of procrastination), it is time to ponder this question again and see what my colleagues think. To see what their vision of a school is and should be; to understand and analyze how different factors can affect how teachers view exactly what the role of a school is.

Context and Methodology

Before analyzing the data, I will briefly explain the context, methodology, the survey that participants completed, and address future limitations and considerations. As the “About Tony” page mentions, I work in Bahrain, a tiny kingdom in the Arabian (or Persian) Gulf. I have been working in this country for 3 years, and am currently at my second school. Bahrain, despite its size (and fitting for the region), is an incredibly diverse place. Over 60% of the population are ex-pats and within the education sector, I work with and know teachers from every continent (not-including Antarctica). This wonderful mixing of backgrounds and cultures is one reason Bahrain can be a rewarding place to live. The opportunity for deep and meaningful conversation abounds as stories are shared and experiences exchanged. This diversity is also why I was motivated to gain the perspective of my colleagues surrounding this question in the first place. School is an incredibly local experience, and because of this, each and every teacher I work with had a different educational journey in vastly different environments. Individual style and personality aside, just the contextual piece of this “study” means that differences in philosophy and vision for education will vary greatly. All teachers share a common bond, yet the approach to teaching and learning is unique to every classroom and separates the unified goals of education from the personal art of teaching.

The survey itself was done through Google Forms and asked respondents to answer 7 questions (5 procedural, 2 theoretical). Respondents identified their names (optional), grade level taught, subject/discipline, years of experience, and nationality. They then answered the following two questions: 1) What is a school? and 2) What is the point of school? The procedural questions were to help me inevitably link answers with the hypothesis that teachers from similar regions of the world or working within similar disciplines would share similar perspectives regarding the central question. The theoretical questions were to help respondents separate the temporal aspects of a school and describe what they felt a school should be.

Procedural Data Collection

To collect data, I sent the survey in an email to every faculty member of my current institution, and additionally sent the survey to one former colleague from the United States. The survey collected 20 total responses, 11 named and 9 anonymous. Out of the 20 respondents, 10% had the most experience in preschool, 25% in primary, 35% in middle school and 30% in high school.

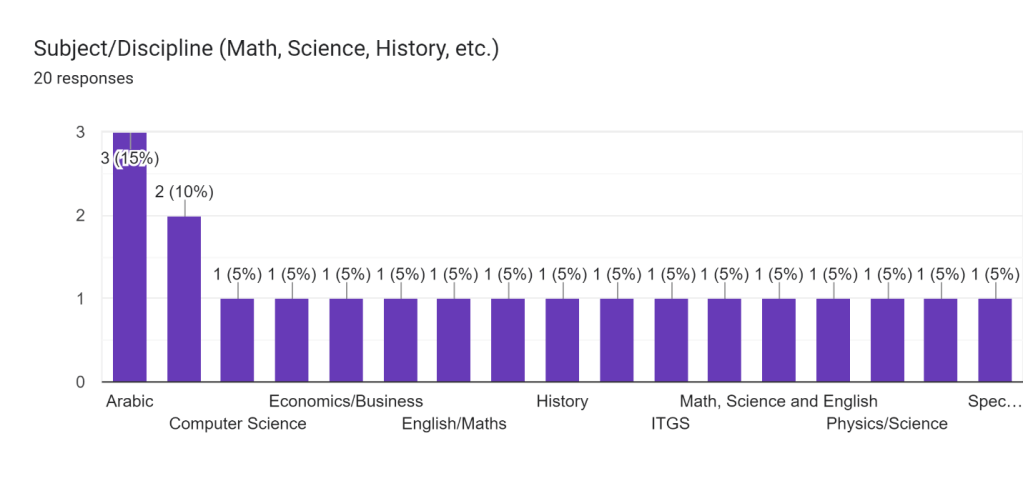

Participants were then asked to identify their discipline, which was not preselected for them. Rather they were allowed to enter in the name of the subject they thought most appropriate. Because of the limitations in the design of this question that soon became apparent during response analysis, I have compiled the results into the following categories and numbers: (italicized categories indicate that at least one respondent also listed courses taught in another italicized subject).

- Math/Science = 6

- English = 5

- Arabic = 3

- History/Social Sciences = 2

- Art = 2

- Generalist/Homeroom = 2

- Computer Science/ITGS = 2

- Special-Ed = 1

- Administration = 1

Teaching experience varied greatly, with the range included one teacher with a single year of experience, while the most experienced respondent had taught for 30 years! (The last bar on this graph was a written answer that identified 6 years of teaching experience, not to be confused with a number greater than 30).

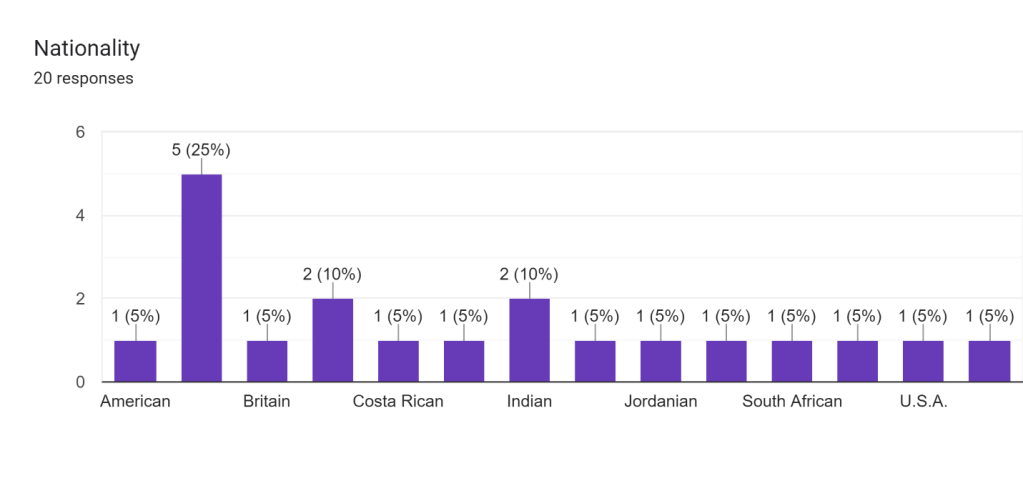

As expected, nationality data was diverse and teachers from 4 continents participated in this study. After aggregating answers that were similar but not written the same (for example, “British” and “Britain”) respondents represented the following nationalities:

- Bahrain: 5

- United States: 3

- Britain: 3

- India: 2

- Jordan: 2

- Syria: 1

- Lebanon: 1

- Costa Rica: 1

- South Africa: 1

- Germany: 1

Limitations and Future Considerations

As this was my first attempt at both designing a survey and analyzing results, there are several things to consider for the future. One of these considerations was the nature of the method for data collection. I had hoped to compare and contrast answers from teachers using the background questions as starters for this analysis. By looking at how answers differed between subjects, years of experience, age, and nationality I had hoped to draw conclusions about the differences culture, age, and educational experience played in the way teachers viewed the role of a school. Google Forms allowed me to aggregate responses and gave me the opportunity to see them all together, while also allowing me to view them individually. Despite this, it became very clear early on that to sort and compare each response this way would be a monumental task and not conducive to the practical concerns of publishing this post. Thus, I chose to read the responses together, without knowledge of who had wrote them and quickly transitioned to language pattern analysis. At first, this pattern analysis was done manually, and included identifying and counting the frequency of certain words, phrases, or ideas. To try and finish the process as quickly as possible (as this post was several months late) I used an AI platform to recognize and isolate the broad trends in the language data. This helped me to comment on patterns and find textual evidence supporting said patterns in a more manageable way.

Another factor that complicated this question was that many primary teachers naturally teach multiple subjects and this made it difficult to organize this information in a way that could make analysis more seamless, when using subject/discipline as a variable from which to draw conclusions.

Yet another consideration was that while this survey was given to a variety of teachers, administrators, and other school-related personnel, it only included 1 response from a teacher outside of my current institution. This will naturally affect the kind of responses received, as experiences inform our opinions. It would be interesting to ask the same question to teachers at other institutions within the country or in other parts of the world.

Asking teachers to write a short 1-2 sentence definition/answer would also have helped respondents get to the root of the central questions and make a decision that is analogous to the daily decision teachers make that inform their practice. This would have also simplified response analysis, as 1-2 sentence answers could have been read faster.

My second question, “What is the point of school?” while successful in asking teachers to identify what they think is real or idealistic about a school, could be worded differently. Instead of, “What is the point of a school,” I think a better question would have been: “What should a school be?” This would have more accurately described the essence of what I was hoping to learn, and in my opinion, could have produced more complex answers, thus giving me more to think about when it was time to draw conclusions.

Theoretical Question Collection and Response Analysis

After analyzing the data, broad trends and similarities emerged. For each question, I will make observations about common language used, conceptual similarities that answers share, and ponder the implications for the structure of schools based on the the answers provided.

Question 1: What is a School?

The word “institution” is mentioned in half the responses and synonyms such as “establishment” and “building” are also mentioned throughout. This suggests that many teachers believe a school is (or perhaps should be) a physical space. Traditionally, this makes sense. In order for learning to be maximized through effective feedback, collaborative/group learning, and the various pedagogical strategies, it is important that learners and teachers share the space together. Put in its historical context, “shared spaces” made sense. Yet, as both COVID-19 and the rapid development of technology have heavily influenced education and removed the physicality of learning, online learning modalities exist in which there is now no need for that shared space. With the multitude of websites, online tools, increase in access to internet and electricity, and cultural adoption of devices in daily life, it is necessary to ask: Does the physical space matter anymore? Does “school” have to be at a “school?” For the teachers in my survey, the answer was mostly “yes.”

Interestingly, one responder separated public and private schools. Their answer is posted below: (response 1).

“Public (state): A necessary institution to ensure the maintenance and development of social fabric via raising the population of a country to a pre-established minimum standard. These schools are for vast majority of society and do not need to cater to external influences other than government directives.

Private: The opportunity for those with the means to have their minimum standard raised and thus obtain a head start among peers for later life. The school operates far more like a business than it does a ‘school’, with parents having increased leverage and means due to stakeholder input.“

Every school is a reflection of the needs of the community it serves. How they are funded and operated impacts everything from the quality and accessibility of resources, relationships between students and teachers, learner engagement, and more. The fact that this was the only answer that highlighted the difference between public and private may suggest that the management structure of the school is not at the forefront of mind to most educators who are naturally focused on learning outcomes, regardless of how the school is operated. Of course if eductors do feel that learning outcomes are impacted by leadership and management, that is a different story.

At least 14 out of 20 answers provided explicitly mention the importance of the “future,” “next stages,” or “later life.” With this in mind it is clear that the majority of respondents believe in the role schools should play in developing students for their adult lives. They clearly believe that schools should and can be institutions that prepare for the future, while operating in the present. This is encapsulated in the “life-long” learning mantra that is now an accepted part of the Zeitgeist in the world of modern education. After all, even traditional public education had a forward-looking vision.

Most of the responses that mentioned the future used it in the context of giving students the knowledge, academic and social skills, and mindset needed for adult life and stated their answers as is. One response highlighted the impossibility of the task of adequately preparing kids for the future, stating, “[school] is a social mechanism that is leveraged to better socialize and equip people in a given context for their future in some way, shape or form. This is an entirely uncertain future, which means the institution itself is already at a disadvantage to achieve a goal that is not entirely clear, nor achievable within these shifting expectations.” (response 2) This teacher is already raising issues that I was hoping to uncover when asking the 2nd question and doubts the ability of schools to adequately prepare kids for the future in the first place. Speaking of, let’s take a look at that second question.

Question 2: What is the point of school?

In general, there are major similarities in the language and tone of the responses in the second question. Several major themes emerged in the answers, including the primary purposes of education, the different ways schools should be “developing” students, and the implicit shortcomings of schools in fulfilling these purposes.

As the question was inherently forward-looking, a majority of the answers emphasized the need for schools to “raise” or “prepare” students for the future. One response summarizes this point nicely, saying, “The primary goal of a school is to facilitate the intellectual, social, and emotional development of students, preparing them for future challenges and opportunities.” (response 3) Many other responses included variations of this point and it is clear from them that most educators hold fast to the belief that they are working towards and with the future. This answer also speaks to a multi-faceted purpose. Schools are there not just to teach academic knowledge and skills, but also to serve their students and the broader community in countless other ways. Educators understand viscerally the need for these additional supports, such as mental health and counseling services, access to classroom supplies, food and medicine, mentorship and guidance, career advice, and more.

This varied approach to student development is generally accepted and may go without saying. It is also an idealistic one that may not reflect the dual responsibility that schools have for individuals and society at-large. Response 3 considers the student strictly as an individual, and the school as a vehicle for that, or any individual to enter adult life. Many of the responses shared this view or approached the question from a similar perspective, like this responder who said the point of school is to, “expose young people to a broad range of academic disciplines and potential areas of interest in the hopes that both a general love of learning, and a specific interest in a possible future career path, will be ignited.” (response 4) While a very well-written answer and something I personally agree with, it’s important we remind ourselves that schools were not always set-up with the goal to “expose” and “ignite.”

Let’s remember that the Prussian model of education, the model which formed the foundation of Western education as a whole, was certainly not designed to inspire the next great artist, philosopher, or tech entrepreneur. In many ways it was created to address the simple political reality that there must be, “a minimal standard of education among a society to help with inequality and giving a government a foundational workforce to develop their economy with. To add wealth to an economy by creating a more highly skilled workforce.” (response 5) This responder is keying on arguably the most fundamental struggle of schools and education alike. If schools were designed with “the country” or “the masses” in mind, how can schools abide by the doctrine of student-centered learning and prepare them for their “future challenges or opportunities?” Essentially, how can schools be both for the masses and for the individual? Maybe the author of response 2 was onto something…

Conclusions and Final Questions

So what is the point of school? How do we create schools that truly cater to the needs of all students? Is that possible? Should we try that? What kind of schools should we build for the next generation of students? These are just some of the questions raised by the respondents in this survey.

Personally, I’ve coalesced my thinking around a few core ideas. First, I do believe that schools require a physical space. There are a number of reasons I believe this. It is a simple human fact that we are social beings. We require connection and relationships and schools are those rare places where an individual receives a multitude of beneficial relationships that can help them grow. As opposed to online or virtual spaces that bring people together artificially, physical spaces like that of a school allow students, teachers and other faculty members to work with each other towards the common goals of learning and growth. These human connections also help combat the uncertainty and anxiety that is a natural part of growing up, important for adolescents especially, who are undergoing physiological changes and forming an identity. Face-to-face feels better than screen-to-screen.

Second, a school should be a place where content and academic skills are simply part of the broader curriculum. Schools should teach other life skills and lessons. This does not mean every school has to offer every program or every subject; that would be impossible. Schools can and should look different, based on the teachers, students, and cultural contexts within they reside. There are countless ways schools can differentiate themselves, whether through pedagogical approaches, the cultural attitudes and beliefs underlying the organization of the school, the types of curriculum offered, and/or more. Regardless, there is much to learn outside of the traditional content knowledge and academic skills.

For me, teaching students about healthy living (exercise, nutrition, sleep, hydration, etc.) should be a fundamental part of their education. Much of the health issues that currently plague our world, such as growing rates of obesity1 and mental and emotional stress can be greatly reduced by simply treating the body with the respect it deserves. Teaching students about financial literacy should also be a required course/subject. Students must understand the impact of their financial decisions on their future, and should learn about various ways to protect and growth their wealth. Lastly, we should also teach them about well-being and responding to the uncertainties, challenges, and anxieties of life. This does not mean we need to teach students about “social-emotional learning” per say. Too much emphasis on how students feel can amplify the uncertainty that already governs their attitudes toward life. Often, too much focus on how we are feeling causes rumination and contributes to existential doubts and guilts that are not conducive for a happy and gratifying life. Still, we can teach students how to respond and act on their emotions in healthy ways.

Third, a school should be a place where students have choices. Traditional schools only have to offer their students a few choices to work towards the goal of a holistic education. Schools can allow students to choose which elective subjects they would like to study. They can allow students to choose and plan school events and initiatives. They can give space for students to choose how to be assessed and on what subjects. Of course, these choices must coincide with local and national standards, while also preparing students for standardized tests that are still is a mainstay public education. Giving students meaningful choices can help them feel more closely connected to the school and helps them learn through experience. As they say, “experience is the best teacher.”

Zooming back out, it is clear that almost all current teachers and administrators surveyed believe in the purpose(s) of school. They believe in the ideal role of an institution that prepares kids for the future. They believe that whether public or private, physical or online, schools should encourage students to be life-long learners. How students are taught to think in this way, the role of the school in teaching them to think this way, the resources accessible for students to fulfill this purpose, and the curriculums that are used will always be up for debate. However, teachers and administrators can agree on one fundamental truth about school: School is for and about the student. The institutions, curriculums, resources, settings, tools, lessons, and supports that each and every school offers should be for the sake of student success. Regardless whether they are public or private, small or large, rich or poor, schools are for the student. With our understanding of the history of public education in the back of our minds, and the eye to the future educators have, we must work to create schools that are houses of wisdom, factories of ideas, and workshops of mastery. So, let’s get to work. Let’s get to learning. Let’s go to school.

References

- “Obesity and Overweight,” World Health Organization, March 1, 2024, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. ↩︎